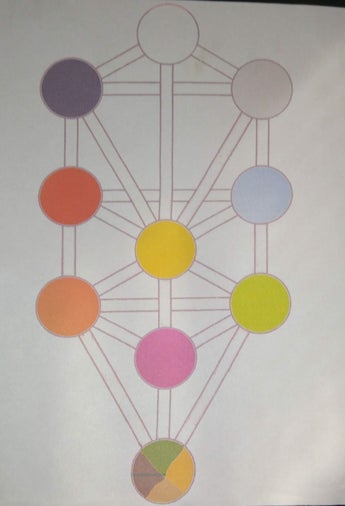

There are Three reasons why the sky is round: likeness, conveniece and necessity. Likeness, because the sensible world is made in the likeness of the archetype, in which there is neither end nor beginning; wherefore, in likeness to it the sensible world has a round shape, in which beginning or end cannot be distinguished. Convenience, because of all isoperimetric bodies the sphere is the largest and of all shapes the round is most capacious. Wherefore, since the world is all containing, this shape was useful and convenient for it. Necessity, because if the world were of other form than round--say, trilateral, quadrilateral, or many sided--it would follow that some space would be vacant and some body without a place, both of which are false, as is clear in the case of angles projecting and revolved.

--The Sphere of Sacrobosco (Trans. Thorndike)

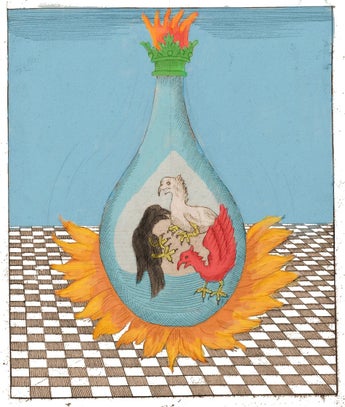

When you wanted God with the same intensity as when you

needed a sex partner, then that God would be with you, because you

would have to find that God or perish in the attempt. This was the

significance of the text. God itself must be your sex partner found

through the mediatorship of another human. This was the way early

mystics understood it. Their love affair with God was sexual in

every implication except physical, and some would have included

that as well.

–WG Gray

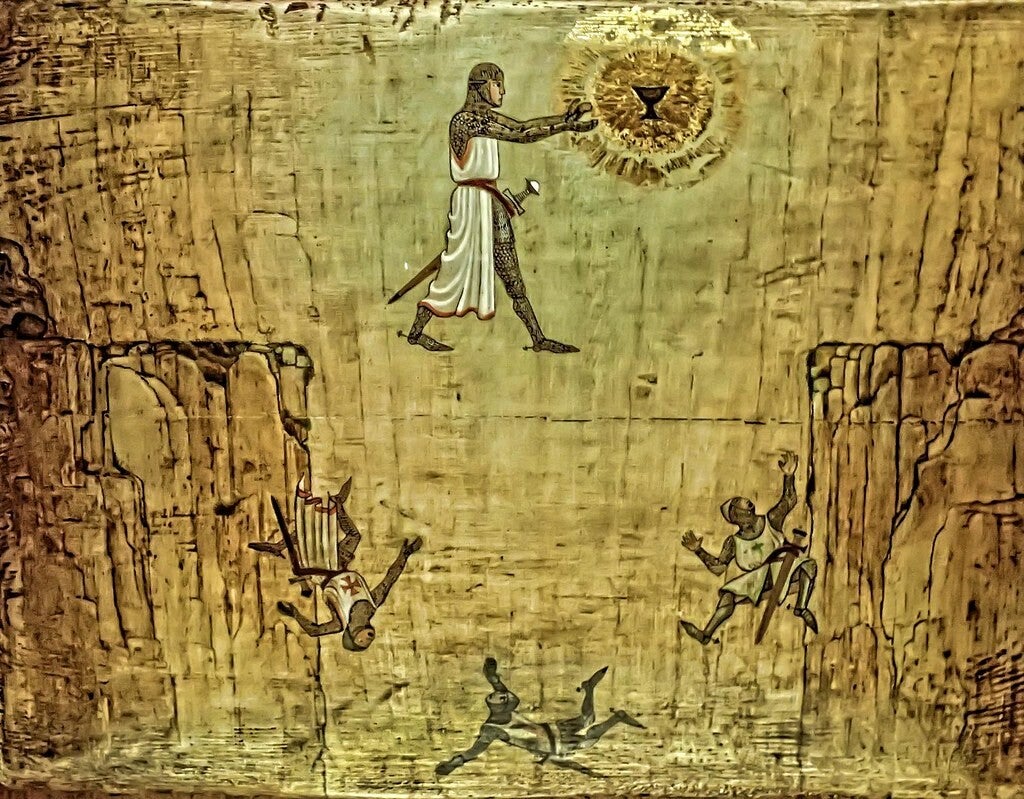

..a table of silver, and the Holy Vessel, coverd with red samite, and many angels about it...and before the Holy Vessel... a good man cloaked as a priest. And it seemed he was at the sacring of the mass.

--Le Morte D'Arthur

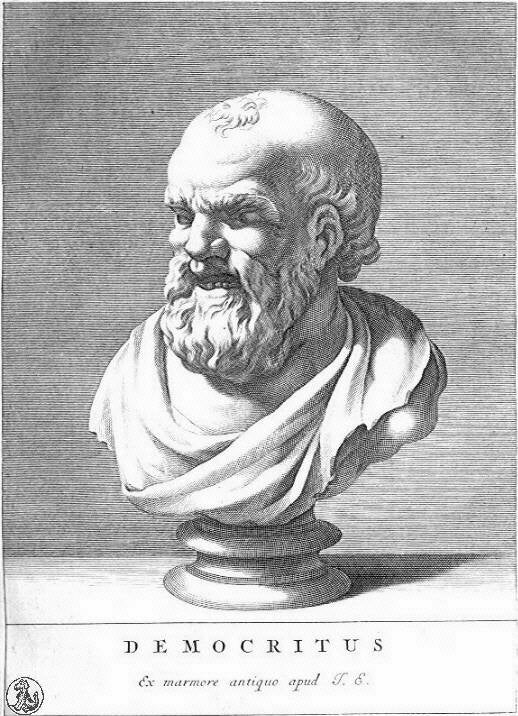

AE WAITE

Father of the Mysteries

Create Your Own Website With Webador